A George Mason University researcher found a strong interest in reporting on how climate change is affecting local communities — and stories that spotlight solutions.

Virginians are hungry for news about climate change.

A recent survey by a researcher with long roots at George Mason University found nearly four in five adults in the state expressed interest in reading about how climate change is affecting their communities — slightly above the national average and on par with states like Minnesota, Oregon and Washington.

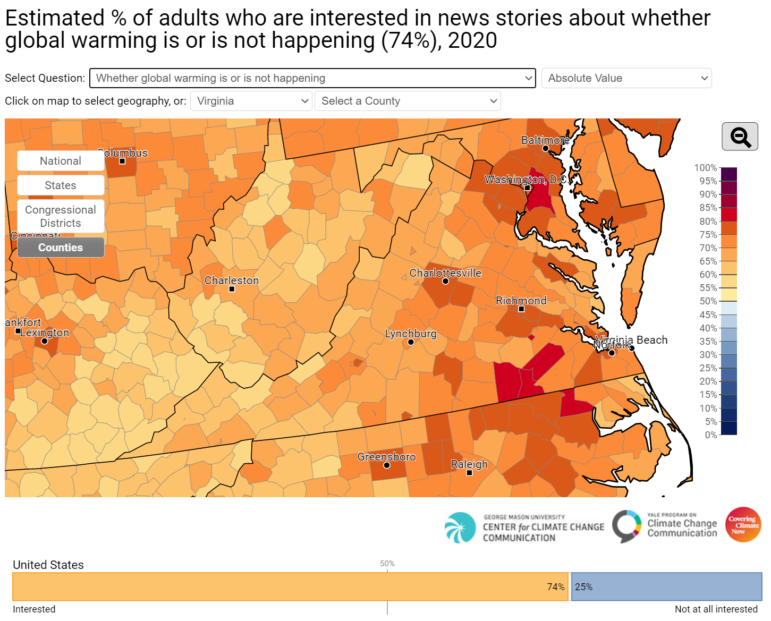

Interest peaks in northern Virginia’s Washington suburbs, Charlottesville, and coastal areas that have long witnessed flooding and other warming impacts firsthand, and it tapers off significantly in historically coal-reliant counties of the state’s mountainous southwestern reaches.

That takeaway is just a tiny slice of the massive amount of data released recently as Americans’ Interest in Climate News 2020. The joint project relies on sets of colorful, detailed, reader-friendly maps to tell the story of how geography shapes people’s interest in climate change.

Professor Edward Maibach, director of the George Mason Center for Climate Change Communication, spearheaded the endeavor. He collaborated with a similar program at Yale University and Covering Climate Now. The latter is a global journalism initiative including more than 400 news outlets.

One driving force was the approach of Climate Week NYC, a late September summit operated by the United Nations and New York City.

“These maps grew out of a brainstorming session several months ago,” Maibach said in an interview. “We’ve known for a long time that people say they rarely or never hear about climate change in the news. Journalists might think they’re covering this, but their audiences aren’t hearing about it.”

The idea is to offer perspective to reporters and editors eager to figure out what type of climate coverage resonates among readers and viewers.

Researchers asked upward of 5,700 adults 10 separate survey questions to gauge their interest in a series of potential climate-related news story topics, ranging from the hyper-local to the planetary.

Queries included the impacts of climate change on a respondent’s local community, elsewhere in the country and around the world. They also covered actions taken or proposed by local communities, the federal government, foreign governments, businesses, and the U.S. presidential candidates to respond to climate change.

News stories about whether climate change was happening or not generated the least amount of interest from survey participants, at 74%.

A screenshot of the Yale Climate Opinion Maps shows the estimated percentage of Virginians who are interested in news stories about whether global warming is or is not happening. View the interactive map of Americans’ Interest in Climate News 2020.

A screenshot of the Yale Climate Opinion Maps shows the estimated percentage of Virginians who are interested in news stories about whether global warming is or is not happening. View the interactive map of Americans’ Interest in Climate News 2020.

“Two things about the takeaway here,” Maibach said. “The climate story that people are least interested in reading about is, ‘is global warming happening or not?’

“And they’re more interested in solutions stories than climate impact stories. It doesn’t mean we don’t still need impact stories, but what this confirms is they’re telling us, ‘Enough about the risks already. Let’s get on with the public dialogue about what we’re doing about it.’ That includes what kind of attention the presidential candidates are paying to it.”

Viewers clicking on the maps can absorb the overall national data picture before zooming in to compare and contrast results at any state, congressional district and county level.

Maibach and his fellow researchers weighted the feedback they collected from close to 6,000 interviewees by deploying a sophisticated statistical algorithm to determine accurate estimates of public opinion in every county, metro area and state.

“Every six months, we interview 1,250 people about various climate topics,” he explained. They bumped that number up by surveying thousands more participants this summer “because you can’t create maps based on 1,250 people.”

Their methodology is a metaphor for exactly the tools that climate scientists call upon to put their information into perspective.

“Scientists know, with incredible accuracy on a large scale, how the climate is changing,” he said. “But they don’t know with precision how it is changing in specific localities.”

The maps known as the Yale Climate Opinion Maps were originally created in 2014. Updates have been rolled out in 2016, 2018, 2019 and now.

Maibach, a professor at George Mason since 2007, is a founding director of the center that produced the maps. He and the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication have a long history of collaboration.

As well, he is known for an innovative project he helped to launch more than a decade ago with funding from the National Science Foundation. He joined with Climate Central, a science communication nonprofit, to figure out how to lure television weathercasters into becoming allies of public climate education.

By 2010, after a survey showed high interest in such an undertaking, he was helping a team of broadcast meteorologists, climate scientists, writers, communication scientists and graphic designers craft a series of short TV segments. Climate Matters, designed to be presented along with the evening weather forecast, touched on extreme heat, hurricanes, air quality, drought, intense storms, human causes of climate change and other subjects relatable to local weather events.

The success of the 2010-2011 pilot program at a TV station in Columbia, South Carolina, turned out to be a welcome education for viewers — and its creators.

“That made an incredible point to all of us,” Maibach said. “News outlets were terrified to talk about climate change because they thought people were raving climate deniers. They figured the channel would be switched.

“But instead of turning viewers away, it earned their loyalty.”

Today, about 950 weathercasters are affiliated with Climate Matters.

Even though Maibach said his latest maps send an obvious message to news outlets that, “hey, they ought to be producing more solutions stories” about climate change, he acknowledges there’s no guarantee such pieces will attract eyeballs.

“When most Americans tell us they rarely read about climate change in the news, is it because it isn’t there? We don’t really know. We do know that climate change is such a tiny, tiny proportion of the news hole that it’s basically a rounding error.

“If the scientists are right and it’s changing our world in dangerous ways, why is that so?”

Original source: Energy News Network