Generation 180

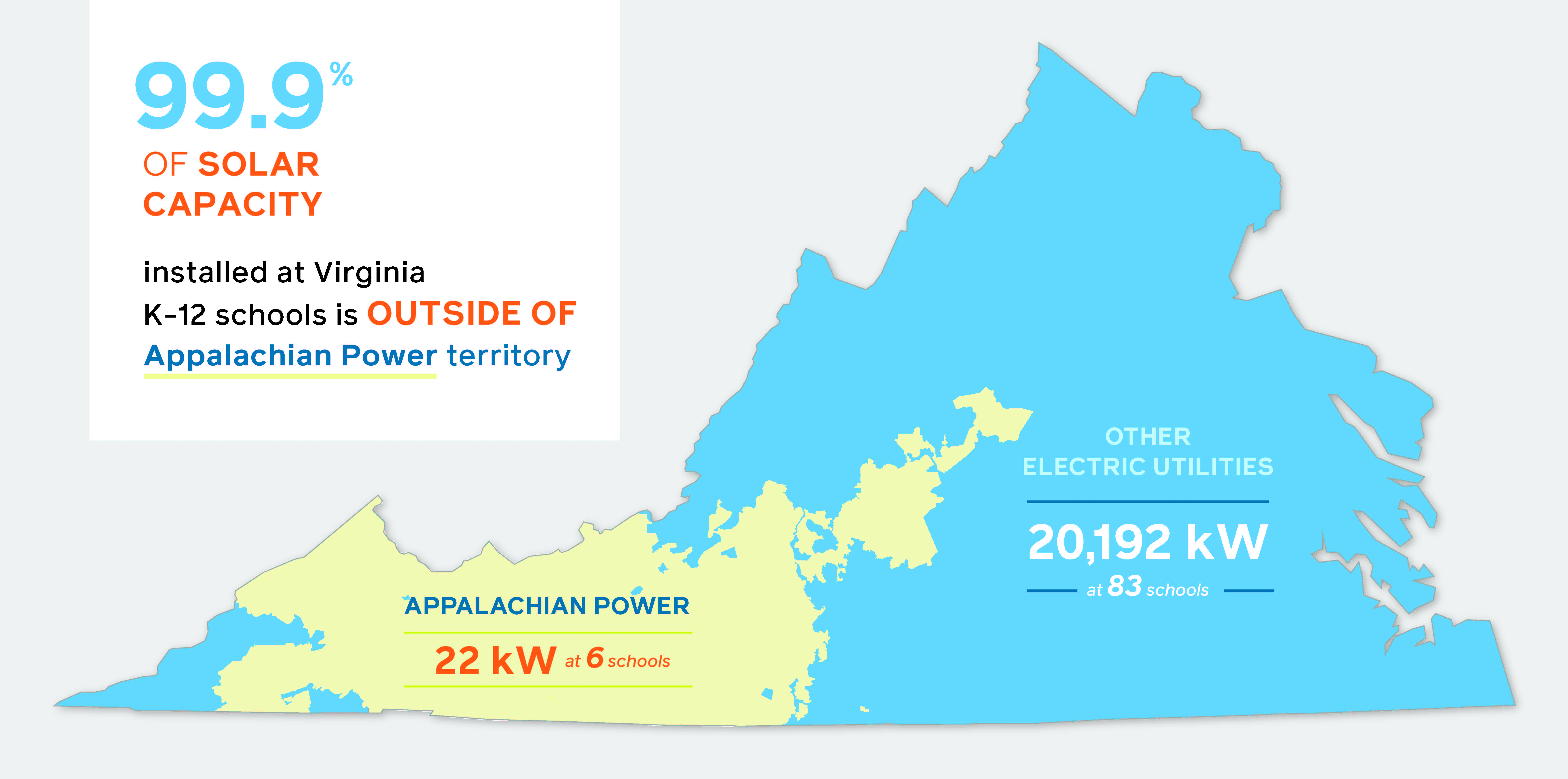

Just 22 kW of the 21,000 kW of solar installed at K-12 schools across Virginia is in Appalachian Power territory, according to research by the nonprofit Generation 180. That’s one-tenth of 1% of the total.

A 2016 agreement between Appalachian Power and local municipalities supersedes the state’s new solar law.

By now, Denechia Edwards figured the rooftop of Ridgeview High School in southwest Virginia would be the highlight of a lesson about solar ingenuity deep in the heart of coal country.

But the 700-kilowatt system proposed in 2018 is still on hold.

That means no $10,000 annual savings on utility bills for Dickenson County Public Schools and no hands-on training for more than 1,000 students.

Instead, Edwards continues to have her patience tested as communities in Appalachian Power’s footprint begin revisiting a soon-to-expire contract that severely limits access to renewable energy. A rider in the 2016 agreement between the utility and public authorities caps territory-wide, net-metered solar systems at a puny 3 megawatts for schools and other government entities.

“We’ve run into a blockage,” said Edwards, whose three titles at her rural district include director of career technical education. “It’s pretty significant for us to be able to do this solar project. Over a 30-year period, we’re looking at saving a million dollars.”

Early on, she served on the Solar Workgroup of Southwest Virginia that selected Ridgeview as one of its original six installations. All have been stymied by policy hurdles.

A steering committee for those public authorities has started meeting regularly to iron out electricity rates and terms of service for the next four-year energy contract with Appalachian Power.

Appalachian Power, part of the giant American Electric Power system, serves 531,677 total customers in Virginia. Dominion Energy is by far the largest investor-owned utility serving the state.

In tandem with the cap on net metering, the current contract is nebulous about power purchase agreements, saying public ratepayers must own and operate the solar array. That’s cost-prohibitive for schools and local governments that count on third-party PPAs.

A typical such PPA allows a solar developer to own and operate an installation. Unlike public schools, developers can take advantage of federal tax credits for solar installations.

Also, the customer isn’t responsible for upfront costs and is charged only for electricity the system produces, usually at a reduced rate. Credits that net metering customers send back to the grid can offset their bill.

The Dickenson district’s budget for this fiscal year is $26.3 million.

“As a small school, we can’t afford this outright,” she said about the need for a PPA. “Solar is a very expensive endeavor.”

Hannah Coman, a staff attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center, said her organization is focused on educating municipalities about the importance of participating in the 2020 contract negotiations.

She is aware that many Virginians are under the impression that solar’s reach will expand everywhere because Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam recently signed the Clean Economy Act and a Solar Freedom bill into law.

“That’s monumental,” Coman said, “because it really changes solar energy policy in Virginia.”

However, many people don’t know that schools, town halls, libraries, landfills, wastewater treatment plants, jails and other public authorities have to negotiate their own energy contracts with utilities.

In Dominion Energy territory, she said, the negotiators have settled on an “elegant solution” that allows public authorities — referred to as non-jurisdictional customers — to follow net metering and PPA measures that apply to residential, commercial and other everyday customers, known as jurisdictional customers.

“But you live in a different world if you live in Appalachian Power’s territory,” she said. “It’s a little bit tricky.”

Language in the current contract about who can own and operate a renewable system needs to be clarified and updated for progress to happen, Coman said.

“At best, it’s ambiguous,” she said. “At worst, it takes a PPA out of the equation. And those are pretty much necessary for schools.”

Helping communities understand what is at stake empowers them to lower or eliminate longtime barriers to solar.

“I feel like solar has recently become something that schools and towns in Appalachian Power territory have become more interested in,” Coman said. “They now have an opportunity to move forward and I hope they can take advantage of it.”

Both the Clean Economy Act and Solar Freedom — which go into effect July 1 — open up the PPA program to all jurisdictional and non-jurisdictional Appalachian Power customers. As well, they boost the PPA program to 40 MW from a current, more restrictive limit of 7 MW.

However, the utility’s contract with public authorities is privately negotiated and its content supersedes state code. So, public entities may or may not have access to the full 40 MW, depending on what is negotiated in the contract.

Meeting June 30 deadline not likely

Rocky Mount town manager C. James Ervin is encouraging public authorities to speak up about their new energy needs, whether it be solar, landfill gas or biomass, so the 3 MW cap can be expanded significantly.

Ervin was elected as chair of the steering committee in 2018. It’s a sub-entity of the Virginia Municipal League and the Virginia Association of Counties. Decades ago, localities in Appalachian Power’s territory called upon those two organizations for guidance in negotiating an energy contract with the utility collectively instead of individually.

“That has saved taxpayers millions and millions of dollars,” he said, and allowed communities to hire informed utility experts for guidance.

Rocky Mount, a Franklin County town of about 4,700, is about 25 miles south of Roanoke in the Blue Ridge Mountains.

The 3 MW limit settled on in 2016 was exhausted by 2019 as times have changed and more and more localities are exploring how to generate renewable energy they can sell back to Appalachian Power.

“As the chief negotiating arm, we want an ever-increasing cap and we want it baked into the overall rate,” Ervin said. “We’re all sort of marching toward a path where we have a smaller and smaller energy footprint.”

Appalachian Power has implied that raising the cap will lead to increases in kilowatt-hour costs because of utility expenditures to adjust and build infrastructure to accommodate more renewables, he said.

“We are completely open to [the utility’s] proposals for fair and reasonable costs and we are not afraid of looking at those figures,” Ervin said. “We are simply trying to negotiate a correct, fair and just rate.”

As part of the contract negotiations, Appalachian Power is in the midst of a cost-of-service study for its public authority customers.

The technical study offers an analysis of how much it costs the utility to provide electricity to different customer groups. It doesn’t necessarily determine rates, but provides relevant discussion fodder for the steering committee.

Ervin predicted that utilities everywhere will be slow-walking rate discussions as “the crystal ball is really foggy now” during the chaos triggered economy-wide by the coronavirus pandemic.

Also, he doesn’t expect contract negotiations with Appalachian Power to be completed by the June 30 deadline. For good or for bad, the language in the current contract will hold until a new agreement is reached.

“We’re not going to see anything until 2021,” he said. “The longer the current rates hold, the more clarity there will be.”

Utility spokesperson Teresa Hamilton Hall said “misinformation that’s circulating about solar and schools” blames Appalachian Power for creating a barrier to solar. It’s unfair to place that onus on the utility, she said.

Schools are subject to the “self-imposed 3 MW limit” because they are part of the group negotiating the contract,” she said.

Hamilton Hall pointed out that localities are in full control of what they want considered during negotiations, including the length of the contract. As well, she added, electricity rates can be adjusted to account for third-party rates if the localities opt to pursue that route.

School solar footprint tiny

Tish Tablan is the program director for Charlottesville-based Generation 180, a nationwide nonprofit intent on linking schools with solar as an energy source and a teaching tool.

Her research through December reveals that just 22 kW of the 21,000 kW of solar installed at K-12 schools across Virginia is in Appalachian Power territory. That’s one-tenth of 1% of the total.

In contrast to that tiny total, she noted that Virginia’s new Solar Freedom measure allows one Virginia homeowner to install a 25 kW system.

While her group is not involved with the current contract negotiations, she and others are “trying to reach local leaders and school decision-makers to give them the right information.”

“We saw the momentum for solar and wanted to capture it,” Tablan said about advances legislators made this session after citizens rallied. “We don’t want to see the doors closing, for southwest Virginia in particular.”

Interestingly, five of the six projects that comprise the 22kW of solar at schools in Appalachian Power’s footprint were 1.2 kW demonstration projects funded in 2018 by a Dominion Energy program called Solar for Students. The remaining 16kW is part of a wide-ranging renewable energy and efficiency project at a public school in Ervin’s community of Rocky Mount. That one was funded by the U.S. Department of Energy; the state Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy; and local school district money.

“The proof is in the pudding,” Tablan said about the need for PPAs. “Schools don’t have a spare million around to spend on solar. They have trouble with budgets and funding.”

Edwards, of Dickenson County Public Schools, is all too familiar with lean budgets.

The school system introduced students to solar several years ago via two demonstration arrays. Dominion paid for one near the pre-engineering building and the state Department of Mines, Minerals and Energy covered expenses for an installation atop the greenhouse.

However, she yearns for all middle- and high-schoolers to be able to supplement their scientific knowledge and expand their career possibilities by watching skilled laborers install the 700 kW system and then tracking its energy production.

“We’ve had a decline in the coal industry,” Edwards said about being poised for an energy transition. “While we want to honor that because it’s such an important part of our heritage and has been our lifeblood for a long time, we have to support our students as we try to move forward.”

Middle-and high schoolers are housed in separate wings of a building constructed in 2015 to accommodate both academic and technical career tracks. Rooftop solar would be a special educational boon for students enrolled in three electives — robotics, pre-engineering and sustainable and renewable technologies.

All of that wishing will have to wait until a new contract is inked between localities and the utility. Edwards has her fingers crossed that the region can soon overcome obstacles blocking solar.

“We’re on the top of a mountain here, so we’re a perfect fit for a solar installation,” she concluded. “It would give us a chance to teach our kids something new and something different.”

Original source: Energy News Network