Lyndsey Gilpin / Southerly

A natural gas pipeline sign in south Louisiana.

This story was produced by Southerly, an independent, nonprofit media organization that covers the intersection of ecology, justice, and culture in the American South.

Dorothy Ingram is among dozens of Raceland, Louisiana residents who say they’ve received few details about a proposed natural gas pipeline that would cut through historic Black churches and graveyards in their community, which sits about 40 miles west of New Orleans.

“We have been treated unfairly and without meaningful involvement,” Ingram wrote in a letter in August 2019 to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which approves interstate natural gas pipelines. “We as a community did not have a meeting in our area to participate in the plan.”

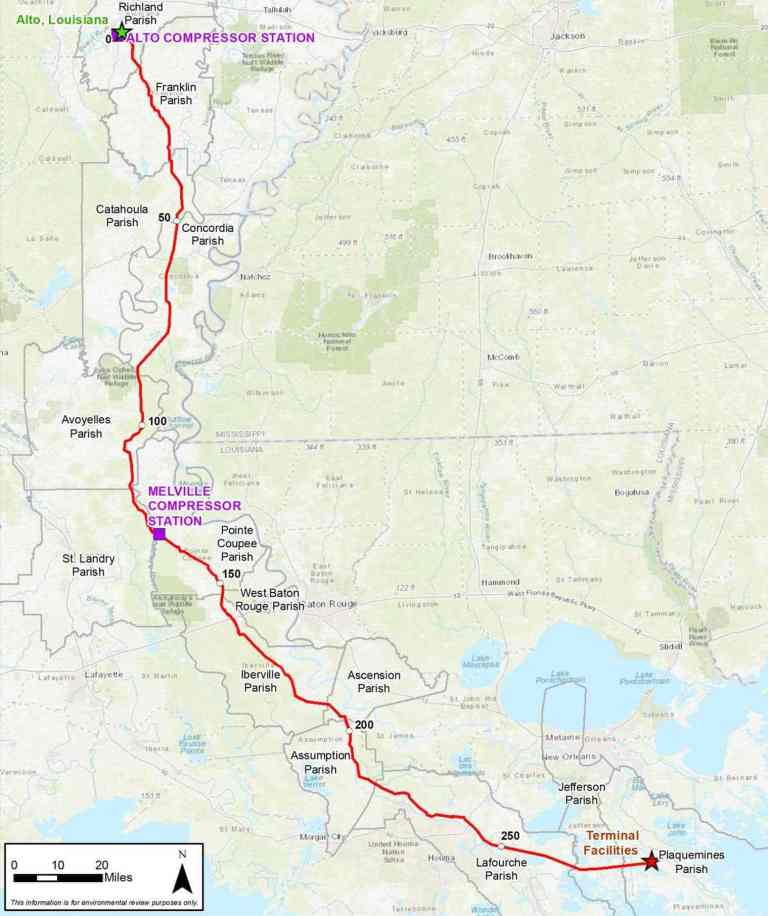

First proposed in April 2019, the 280-mile Delta Express pipeline would be built through 14 parishes, connecting an existing natural gas pipeline in northern Louisiana to a liquid natural gas facility in Plaquemines Parish — Louisiana’s southernmost parish, where coastal erosion and sea level rise are expected to swallow up 55% of land without coastal restoration projects. The company, Venture Global, has not held a meeting to seek public comments in Lafourche Parish, which includes Ingram’s neighborhood.

The pipeline is still in an early stage of permitting: Venture Global hasn’t submitted its formal application to FERC or acquired state permits. But emails show that the company has tried to influence state and federal permitting agencies by employing a Louisiana lawmaker, Rep. Ryan Bourriaque, R-Abbeville, who is also vice chair of the House Natural Resources and Environment Committee.

Emails obtained through a public records request by the Energy and Policy Institute reveal that Bourriaque negotiated with the state’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, or CPRA, about a separate Venture Global pipeline crossing a Mississippi River levee CPRA is planning to elevate. Bourriaque also sent a template letter for other Louisiana lawmakers to send to FERC in support of the Delta Express pipeline.

“Regular citizens are having a harder time voicing their opposition to projects that impact them directly,” said Energy and Policy Institute researcher Itai Vardi. “At the same time, you see that there’s an acceleration with industry insiders using their cozy relationship with elected officials to influence decisions.”

Photo credit Venture Global LNG via Southerly

Photo credit Venture Global LNG via Southerly

According to financial disclosure forms, Bourriaque started working as vice president of development for Venture Global shortly after he was elected in 2019. He reviewed CPRA provisions for allowing a liquid natural gas export project to be built along a Mississippi River levee before they were sent to the Plaquemines Parish permit coordinator.

CPRA Chairman Chip Kline emailed Bourriaque directly about the project. “I know this is important to Venture Global, and I completely understand the sense of urgency,” Kline wrote. “I would be happy to meet in person next week or have a conference call to discuss the path forward and the remaining steps in the process.”

Rachel Haney, the agency’s spokesperson, said that Bourriaque’s position on the House Natural Resources and Environment Committee did not influence communications with him about the project. “CPRA regularly coordinates with applicants to ensure concerns over levee impacts are adequately addressed and avoided,” she said. A letter from the CPRA to the parish’s permit coordinator states that the LNG project won’t compromise the proposed levee.

Bourriaque told Southerly that most legislators hold full-time jobs outside of public office, which is considered a part-time position that pays a base salary of $16,800. Before Venture Global, he was the parish administrator for the Cameron Parish Police Jury.

But Bourriaque’s emails with the CPRA are evidence of an elected official lobbying state entities on behalf of private interests, said Naomi Yoder, a science review specialist for the environmental group Healthy Gulf. “I think that would be pretty standard if he was representing his district,” Yoder said. “But he’s representing a company. He’s trying to wear both hats.”

Asked if he would support the project if community members in his district were opposed to it, Bourriaque told Southerly, “I would rely on the relevant facts [and] feedback from constituents and make a determination on how to proceed accordingly.”

As of March, FERC has received 147 public comments on the Delta Express pipeline and LNG export facility. Of those, nearly all — 127 — were from concerned citizens opposing it. Some are landowners who don’t want a pipeline crossing their land. Others are elderly residents concerned about the project’s health impacts. Most came from residents living in the predominantly Black neighborhood of Lewiston in Raceland; many worry about damage to historic sites.

An attorney for the Tunica-Biloxi Tribe of Louisiana, a federally recognized tribe whose citizens mostly reside in Avoyelles and Rapides parishes, asked the federal permitting agency to expand its consideration of the pipeline’s impacts to environmentally and culturally sensitive areas. The path of the proposed pipeline crosses the “heartland” of the tribe and could contain burial grounds, said Ray Martin, the tribe’s attorney.

FERC has already identified several potential issues with the pipeline, including impacts to wetlands, air quality, and environmental justice communities. The Tunica-Biloxi also asked FERC to consider the pipeline’s impact on climate change and sea level rise — especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. “The tribe really has concerns about expanding fossil fuel use when we have a global respiratory pandemic occurring,” Martin said.

While communicating with CPRA about the project, Bourriaque also emailed lawmakers representing 14 parishes the pipeline would cross, asking them to send letters of support for the Delta Express pipeline to FERC. He included a template letter for them to mimic.

Among those who received the boilerplate letter were Louisiana House Republicans Clay Schexnayder and Johnny Berthelot. FERC received nearly identical letters of support from them, as well as Sen. Richard Ward, R-Port Allen. Neither Schexnayder, who is the House speaker, nor Ward, responded to requests for comment. Berthelot left office in 2019.

The fossil fuel industry’s use of ghostwritten letters to show they have the support of local elected officials for projects is not new, according to Vardi, from the Energy and Policy Institute. He called the practice “anti-democratic,” saying the letters are essentially industry documents meant to look as though they were written by lawmakers.

Bourriaque said he checked with the former Clerk of the Louisiana House to verify that sending the template was allowed under legislative rules. But Louisiana Board of Ethics administrator Kathleen Allen said Bourriaque did not consult with her.

Bourriaque defended his actions, claiming that companies frequently use such templates. “The template is just a suggestion, and of course it would be voluntary for that individual to submit a response,” he said.

Louisiana lawmakers frequently align themselves with petrochemical companies, and the state has cracked down on opposition to oil and gas projects. Louisiana made trespassing on “critical infrastructure” a felony in 2004 and added pipelines to that list in 2018.

The federal government is also moving to make it more difficult to slow down pipeline construction. In July, President Donald Trump’s administration moved to weaken the National Environmental Policy Act, or NEPA, which requires federal agencies to consider the environmental impacts of infrastructure projects such as pipelines. This could have a disproportionate impact on communities in the South, where most new interstate pipelines are being proposed.

The changes — like imposing a deadline for environmental assessments — are expected to make public participation in fossil fuel projects more difficult by giving residents less time to learn about projects and provide comments on their possible impacts, Vardi said. If permits for the Delta Express pipeline are approved, residents who do not believe their concerns were addressed could file a lawsuit against the permitting agencies, but opponents have not yet mounted any such legal challenge.

The NEPA changes would allow agencies more “wiggle room” to argue that climate change impacts are too remote and speculative to require analysis, said Michael Burger, executive director of Columbia Law School’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law.

“The climate crisis is here, it is real, and it is happening,” Burger said. “It is essential that the federal government assess and disclose how its permitting and licensing decisions contribute to climate change, and consider ways to avoid or mitigate those contributions.”

Sara Sneath is an award-winning environmental reporter based in New Orleans. Email her tips at saraksneath@gmail.com and follow her on Twitter @sarasneath.

Original source: Energy News Network