Photographs by Tamir Kalifa for The New York Times

For over a decade, the Permian Basin in Texas and New Mexico has been the epicenter of the American oil boom. Now, it’s the epicenter of its demise.

People here have been through plenty of recessions, but nothing prepared them for the coronavirus and its economic devastation.

‘This Feels Very Different’

By Tamir Kalifa and

May 1, 2020

MIDLAND, Texas — In just over a month, scores of drilling rigs have been dismantled and tucked away in storage yards. Pump jacks, those piston pumps that lift crude out of the ground, have seesawed to a standstill as operators shut down wells.

Oil field workers who dined on strip steak and lobster before energy prices went into a tailspin in March are now standing in line at a local food bank for the first time.

As the coronavirus spreads around the world, people are no longer commuting to work, flying on planes and going on cruises, smothering the demand for oil.

“We’ve had our ups and downs, even over the last 20 years, but this feels very different,” said Matthew Hale, president of S.O.C. Industries, a pump truck and chemical services company that has operated in the Permian for 19 years. “We’re concerned about our industry, survival and what survival is going to look like.”

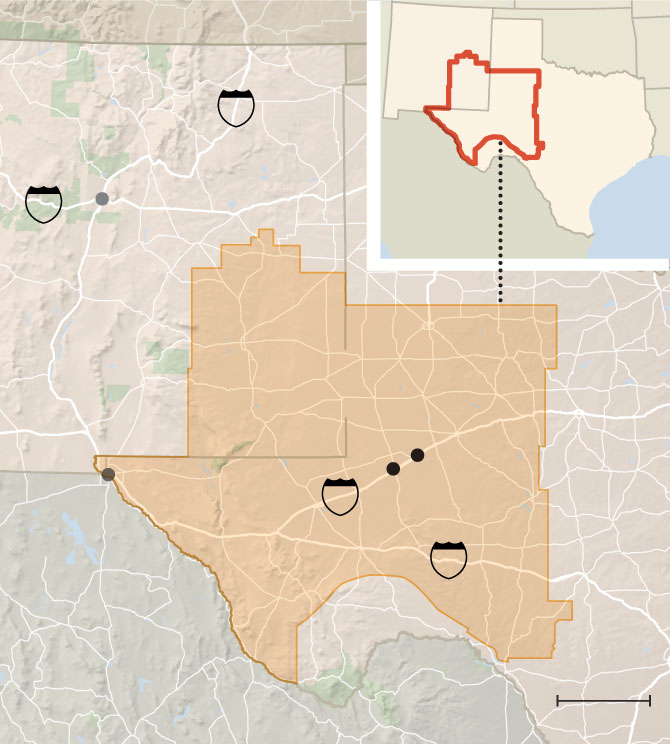

The Permian Basin, which stretches across Texas and New Mexico and is almost as big as Britain, accounts for one out of every three barrels of oil produced in the United States.

The region has a storied history. It provided much of the oil for the American and Allied effort during World War II. In the 1970s, the basin created so many millionaires that many drank champagne out of cowboy boots and had trouble finding places to park their private planes.

That was followed by a crash, after which a popular bumper sticker appeared everywhere: “God Grant Me One More Oil Boom and I Promise Not to Screw It Up.”

N.M.

OKLA.

25

TEXAS

Albuquerque

40

MEXICO

NEW

MEXICO

PERMIAN BASIN

TEXAS

Midland

El Paso

Odessa

20

10

MEXICO

100 miles

Another oil boom did come, as Permian production in recent years spurred a global glut, stole market share from Saudi Arabia and Russia and eventually sparked a price war this year. This boom, too, is ending.

Most companies operating in the Permian have already shut at least 10 percent of their wells, and with local spot prices down to just $5 a barrel, smaller companies are planning to shut all their wells in the coming weeks, executives said. Refineries are running out of storage even as they wind down operations, at least temporarily.

Oil from the Permian supports 10 percent of the Texas economy, including production, services, shipping and refining. But as the world is stuck with too much oil, and too little demand, this area is experiencing a double shock not seen in modern times.

One barometer of the collapse is the local drilling rig count: Last week, it dropped by 37, leaving 246 operating, down from 460 a year ago.

Executives predict 100 more will be gone by the end of the year.

“The futures market is telling us no one should be drilling any wells,” said Scott Sheffield, chief executive of Pioneer Natural Resources, a major Permian producer.

“I don’t think we’ll see a lot of drilling until W.T.I. goes back to $35-$40,” he added, referring to the West Texas Intermediate benchmark price, which has been trading around $20 a barrel. It briefly dropped below zero in April for the first time.

Big companies like Exxon Mobil and Chevron will probably keep producing but at lower rates of growth. And as drillers slow down, it will leave an entire network of suppliers, truck drivers, repair shops and scores of other companies adrift.

The Permian produced five million barrels of oil each day early this year, from a modest 850,000 barrels a day at the dawn of the shale revolution in 2007. Producers say output will go down by at least a million daily barrels by the end of the summer, and may end 2021 as low as 3.5 million barrels a day.

Since the Permian began producing oil in the early 1920s, booms and busts have been an unpredictable yet recurring certainty, like the tumbleweeds that blow across the desert.

Long-abandoned ghost towns are strewn across the arid landscape, reminders of the toll of past oil-price collapses. During the Great Depression, when oil prices sank to 13 cents a barrel (about $2 in 2020 dollars), and again in the 1980s when crude dropped nearly 80 percent, most oil producers in the Permian and nearly every major Texas bank were devastated.

The last few weeks have felt like eerie reminders of that past.

As workers are laid off and sent home, trailers that serve as dormitories for crews on drilling sites have been sitting vacant.

A family waiting to pick up items from Walmart in Odessa. Local business leaders say that as much as a third of the work force in the Midland-Odessa area could eventually lose their jobs.

The Permian made a miraculous recovery over the last decade as the vanguard of the fracking boom that helped the United States approach its long-sought goal of energy independence.

Exxon Mobil returned, and Chevron, BP and Royal Dutch Shell all began to invest heavily as the Permian became the hottest oil play in the world. Struggling elsewhere, Exxon Mobil and Chevron have bet much of their futures on this old field.

Now, only 26 crews are fracking in the Permian, down from 47 in March and 127 in January.

“People don’t know how to react yet,” said Thomas Bruder, a senior manager at ProPetro, a major hydraulic fracturing and well cementing company. “We’re taking it day by day.”

Oil executives are desperate to save their businesses, many of which are overextended with debt. More than 10,000 workers have already been let go or furloughed in and around Midland and Odessa, the industry’s hubs in West Texas. Four times as many might ultimately lose their jobs, executives say.

“The pricing is so low we cannot possibly break even and pay our people,” said Jim Wilkes, president of Texland Petroleum, which has been in business since 1973. The company has run out of buyers for its production of 7,000 barrels a day and plans to shut off its 1,211 wells over the next few days.

“We’re going to have to shut down our production,” Mr. Wilkes said.

The human cost of the layoffs is just starting.

In mid-March, during his last lucrative week as a “hot shot” truck driver before the downturn, Bill Cunningham, 62, clocked over 2,000 miles on five runs delivering loads of casing and tubing around the Permian.

Last week, Mr. Cunningham climbed into his tuxedo-black one-ton Ford F-350 pickup for only two round trips from Odessa to Midland and back, totaling 120 miles. One was to deliver six pipe couplings. The other was to pick up a check.

“Guys like me who are up in their 60s, they’re not going to get hired in a lot of places,” said Mr. Cunningham, who has seen five booms and busts since moving to Odessa in 1979. “That’s the only thing that I’ve got, that I can do,” he said. “We’re not going to starve to death tomorrow, but we might the next day.”

Tamir Kalifa reported and photographed from Midland and the surrounding areas. Clifford Krauss reported from Houston.

Original source: New York Times