Allen Best

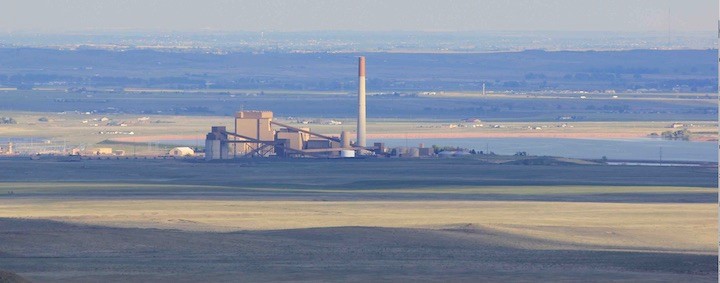

The 280-megawatt Rawhide coal plant north of Fort Collins.

Platte River Power Authority expects fully eliminating emissions will require more distributed resources and changes to how it manages peak demand.

After quietly taking a lead in the race to decarbonize Colorado’s electricity supply, a Fort Collins-based power wholesaler has begun plotting how to eliminate the final and most difficult 10% of emissions by 2030.

Platte River Power Authority is already nearing 50% carbon-free power thanks to major investments in wind and solar projects, with more on the horizon, including a 22-megawatt solar farm expected to come online this month.

As for that last 10%, though, the answers may come not from distant wind farms but instead close to home — literally — and include a pivot in thinking about how the utility maintains a reliable supply of electricity at all times.

“Right now, production chases the load,” said Dave Hornbacher, executive director of electric services for the city of Longmont, one of the four municipalities that comprise Platte River. “When we come home and turn on the light and do our laundry and turn on the oven, those things can happen all at once. A traditional power company ramps up the resources necessary to answer that very immediate need.”

But with high levels of variable renewables, demand will need to be contoured to better match supplies. This will require more thoughtful interaction between consumers and power sources. Can your electric car be programmed to charge when the blustery wind makes electricity plentiful? Can household batteries store cheap renewable energy to power air conditioners on hot afternoons?

The final steps toward 100% carbon-free power likely will involve neighborhood-level energy production and storage, stepped-up energy efficiency, and a “smarter” and more interactive electrical grid, Hornbacher said, all with a goal of synchronizing demand and production.

Pushing renewables, storage

Utilities in Colorado and elsewhere have traditionally met maximum electricity demand by building bigger coal-fired power plants. Particularly since the 1990s, they’ve been aided by the addition of fast-ramping gas-fired plants. That generation was sized to reliably meet the maximum demands — all the while creating pollution, both of carbon dioxide and other exhausts.

Platte River, which serves Longmont, Loveland, Estes Park, and Fort Collins, has similarly depended on fossil fuels. It operates the 280-megawatt Rawhide coal plant north of Fort Collins, and also imports electricity from the Craig Generating Station, of which Platte River has an 18% ownership stake in units 2 and 3. All these units must be closed by the end of 2028, the Colorado Air Quality Control concluded in November in a ruling expected to be finalized this month.

Now come renewables, carbon-free and mostly less expensive. Utilities have integrated them into power supplies at higher and higher levels without sacrificing reliability or raising costs. But there are limits, at least on local and regional levels. The sun goes down with great reliability every night. Even in places where it seems like the wind blows all the time, well, sometimes it doesn’t.

In 2018, when Platte River embraced the 100% carbon-free goal, the utility hovered around 30% non-carbon sources. In its resolution, directors identified nine advancements that must occur in the near term to achieve the 2030 goal. They include matured battery storage performance and declined costs and improved performance of distributed generation resources.

The resolution also identifies the need for a regional energy market. Such markets by a regional transmission organization can more efficiently coordinate deliveries of renewable energy across broad regions. One proposal calls for strong connections with California and other Western states. Another idea sees stronger links to states of the Great Plains.

Environmental advocates were peeved recently when Platte River directors adopted a resource plan that identifies the possible need for additional natural gas combustion by 2030 to replace the lost coal generation. They accused Platte River of walking away from the 100% carbon-free resolution.

Fort Collins Mayor Wade Troxel, who chairs the board of directors for Platte River, said critics missed how much can change in just four years. He points to Platte River’s 2016 resource plan, which failed to foresee tumbling wind and solar prices. Nor did it assume Platte River would surpass 50% renewable generation by 2022.

Symbolically, a 30-megawatt solar farm backed with two megawatts of battery storage now operates adjacent to the Rawhide plant. It will be augmented this month by the 22-megawatt farm, Rawhide Prairie. Other projects could put Platte River at 60% non-carbon sources by the end of 2023.

The investments have put Platte River at the front of the pack among larger utilities in Colorado, nearly all of which have voluntarily committed to reducing emissions at least 80% by 2030 compared to 2005 levels. “It has become a race to the top,” said Zack Pierce, the special climate and energy advisor to Colorado Gov. Jared Polis, on a recent webinar.

Some, like Holy Cross Energy, a co-op serving the Vail and Aspen areas, have also started tinkering with steps to enable complete decarbonization. The co-op may achieve 80% to 85% non-carbon energy by 2024.

Troxell sees being a nonprofit as an advantage for Platte River over privately owned utilities like Xcel and Black Hills Energy because they have no need to deliver profits to investors.

All four municipalities in Platte River have also adopted strong climate action goals. Size may also be to its advantage to Platte River, which accounted for 5.7% of the state’s electrical sales in 2018, fourth highest among the state’s utilities. A single project, such as the 225-megawatt Roundhouse wind farm that began producing this past summer, can have a significant impact.

Troxel, a professor of mechanical engineering at Colorado State University’s School of Biomedical Engineering, began getting interested in energy systems in about 1995. That interest led him and two former students to form a company, Sixth Dimension. The company produced power generation for buildings, using primarily diesel generation, but some solar. The intent was to allow the businesses to monetize the cost savings. The company succeeded and was sold to a larger company, and Troxel returned to the faculty at CSU.

The idea of dispersed generation integrated into the grid to achieve maximum value lingers in what Platte River will be exploring in the coming years. A decade-old smart-grid infrastructure project in Fort Collins, FortZED, provides a foundation for the work lying ahead. A $6.3 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy, part of the federal stimulus package of 2009, got the project off the ground, bolstered by grants and other assistance from 13 community partners.

One component involved testing technologies that reduced peak energy use and integrated renewable energy, such as solar panels, on the CSU campus and Old Town district. Another element called Lose-a-Watt sought to double energy efficiency. A third set out how to demonstrate how a hybrid DC microgrid could improve efficiency, increase renewable production and transform how buildings interact with the distribution system. A fourth component tested how behavior change and more efficient equipment could reduce the energy footprint of a building on the CSU campus.

The project finally wound down in 2017, at a final cost of $13 million, having helped reform ideas about the integration of renewable energy and improved energy efficiency.

In Longmont, Hornbacher sees overlapping challenges ahead. The first step is shaving peak demand through tools such as time-based pricing. Can changes in pricing encourage customers to hold off running washing machines or other appliances until times when renewable energy is abundant?

Many utilities already have rate structures that attempt to shave peak demand. Xcel Energy’s critical peak pricing program, for example, offers large-volume users the opportunity to save up to 5% off their annual costs by agreeing to curtailments during critical peak times. It has several such programs.

Fort Collins already has an extensive program to reshape demand. “When you use electricity is as important as how much you use,” the city’s utility’s website says in explaining its time-of-day pricing schedule. The peak time is 5 to 9 p.m., when rates are 22 cents per kWh compared to 7 cents at other times.

The Smart Electric Power Alliance, a nonprofit dedicated to assisting the electric power industry’s transition to “a clean and modern energy future,” has been enlisted to help Platte River sort through the complexities and uncertainties.

Technology may deliver many answers. A subcommittee of directors has to deliver a strategy to the fuller board in mid-2021. The utility also recently began an effort to engage customers in the four cities in conversation. The goal is partly to educate consumers about what lies ahead during the next decade but also to solicit ideas. Those conversations, Hornbacher said, “will probably involve things we haven’t talked about or even thought about yet.”

Original source: Energy News Network